Getting to know Node's child_process module

How to Call git, cpp, sh, Etc., from a Node.js Script

Node.js is one of the most powerful platforms for managing resources on our computers and has become more and more popular over the years ever since it was released. As much as it’s great, and with all the love and respect that I have for it, Node.JS alone is not enough.

Despite NPM’s evolved ecosystem there are more tools out there which exist outside of it for a longer time, thus they do what they do better than any Node.JS package; such as opencv — an open source computer vision utility library which was developed for C++, Python, and Java (not for Node.JS).

In addition, Node.JS exists for a very general purpose while some tools exist solely for a single purpose; such as git — which exists for the purpose of version controlling.

Accordingly, I’ve decided to write an article about Node’s child_process module — a utility module which provides you with functions that can create and manage other processes.

As you probably know, our typical OS has different processes running in the background. Each process is being managed by a single-core of our CPU and will run a series of calculations each time it is being ticked. As such, we can’t take full advantage of our CPU using a single process, we would need a number of processes that is at least equal to the number of cores in our CPU. In addition, each process might be responsible for running a series of calculations of different logic, which will give the end user a better control over the CPU’s behavior.

Accordingly, if until this very day you’ve been writing Node scripts which don’t involve any

reference to processes at all, you might have been doing it wrong, because you’ve been limiting

yourself to a single core, let alone to a single process. Node’s child_process module exists to

solve exactly that; it will provide you with utility functions that will provide you with the

ability so spawn processes from the main process you’re currently at.

Why is this module called child_process and not just process? First, not to confuse with the

main process instance global.process, and second, the child process is derived from the main

process, which means that both can communicate - the main process will hold streams for the child

process’s std types, and they will both share an ipc channel (“Inter Process Communication”

channel; more on that further this article).

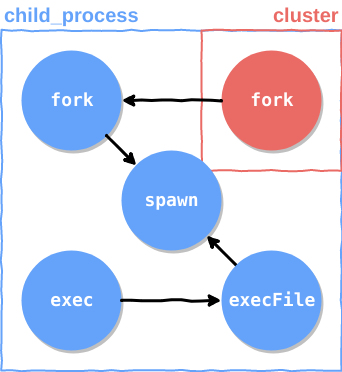

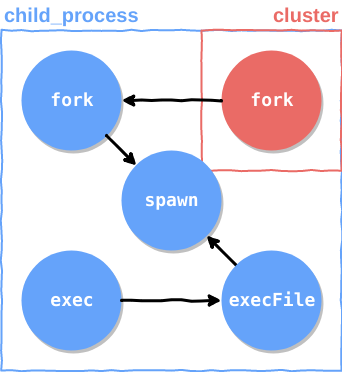

The child_process API

The child_process module provides us with utility functions whose logics are stacked on top of one

another. The most basic function is spawn():

const { spawn } = require('child_process')

spawn('git', ['log'])Docs: spawn

The spawn function will spawn a new process of git log type. The first argument of the function

represents a path for an executable file that should start the process, and the second argument is

an arguments vector that will be given to the executable. The returned process object will hold a

property for each std type represented as a Stream: .stdin - WriteStream, .stout - ReadStream

and finally .stderr - ReadStream. Accordingly, if we would like to run git log through a Node

process and print it to the console we would do something like the following:

const { spawn } = require('child_process')

spawn('git', ['log']).stdout.pipe(process.stdout)Or if we will take advantage of the last options argument, we could do the following:

const { spawn } = require('child_process')

spawn('git', ['log'], {

stdio: 'inherit' // Will use process .stdout, .stdin, .stderr

})Note that every

child_processfunction will also have a “sync” version of it (e.g.spawnSync()), but assuming that you’re already familiar with synchronous and asynchronous functions in Node, I’m going to skip that for the sake of simplicity.

The next function on the list would be the execFile(). As implied, it will execute a given file

path, just like spawn()does. The difference between the 2 though, is that unlike spawn() which

returns a bunch of streams, execFile() will parse the streams and will return the result directly

as a string:

const { execFile } = require('child_process')

execFile('git', ['log'], (err, out) => {

if (err) {

console.error(err)

} else {

console.log(out)

}

})Docs: execFile

Here’s a snapshot of Node’s source code that proves that execFile() is directly dependent on

spawn():

exports.execFile = (file /* , args, options, callback */) => {

// ...

const child = spawn(file, args, {

cwd: options.cwd,

env: options.env,

gid: options.gid,

uid: options.uid,

shell: options.shell,

windowsHide: options.windowsHide !== false,

windowsVerbatimArguments: !!options.windowsVerbatimArguments

})

// ...

}Source: lib/child_process.js

As bash is vastly used as the command line shell, Node provided us with a function that will span

an instance of bash and execute the given command line. This function is called exec() and it

returns the stdout as a string, just like execFile()does:

const { exec } = require('child_process')

// Will print all commit messages which include foo

exec('git log --format="%s" | grep foo', (err, out) => {

if (err) {

console.error(err)

} else {

console.log(out)

}

})Docs: exec

Here’s a snapshot of Node’s source code that proves that exec() is directly dependent on

execFile(), which makes it indirectly dependent on spawn()

exports.exec = (/* command , options, callback */) => {

const opts = normalizeExecArgs.apply(null, arguments)

return exports.execFile(opts.file, opts.options, opts.callback)

}Source: lib/child_process.js

In other words, the core of exec() can be implemented like so:

const { execFile } = require('child_process')

exports.exec = (command, options, callback) => {

return execFile(`bash`, ['-c', command], options, callback)

}Often times, we would just spawn another Node process which would execute another script file, thus,

Node has provided us with a function that is bound to Node’s executable file path, called fork():

const { fork } = require('child_process')

fork('./script/path.js')Docs: fork

What’s nice about this method is that it will open a communication channel between the main process

and the child process (known as ipc - Inter Process Communication), so we can be notified regards

the child process’s status and act accordingly:

/* Parent process script */

const { fork } = require('child_process')

const n = fork(`${__dirname}/child.js`)

n.on('message', m => {

console.log('PARENT got message:', m)

})

// Causes the child to print: CHILD got message: { hello: 'world' }

n.send({ hello: 'world' })

/* Child process script - child.js */

process.on('message', m => {

console.log('CHILD got message:', m)

})

// Causes the parent to print: PARENT got message: { foo: 'bar', baz: null }

process.send({ foo: 'bar', baz: NaN })Source: lib/child_process.js

Now back to what I’ve said at the beginning of this article. Each process uses a single core of our

CPU, hence, in-order for our Node script to take full advantage of our CPU we would need to run

multiple instances of Node, each one would have its own process. But how do we manage the work

distributed between the core?! Luckily, the OS does that for us, so by calling the fork() method

we actually distribute the work on different cores.

Following this principle, a common use-case would be distributing the work of the script that we’re

currently at. So rather than calling the fork() method with the current script file path, we can

just use the cluster module, which is directly related to child_process because of the reason

I’ve just mentioned, and call the cluster.fork() method:

const cluster = require('cluster')

if (cluster.isMaster) {

const n = cluster.fork(`${__dirname}/child.js`)

n.on('message', m => {

console.log('PARENT got message:', m)

})

// Causes the child to print: CHILD got message: { hello: 'world' }

n.send({ hello: 'world' })

}

if (cluster.isWorker) {

process.on('message', m => {

console.log('CHILD got message:', m)

})

// Causes the parent to print: PARENT got message: { foo: 'bar', baz: null }

process.send({ foo: 'bar', baz: NaN })

}Docs: cluster

As you can probably notice, the cluster API has some extra logic in addition to a regular

process, but at its core it’s just another process which was created by child_process. To prove

that, let’s take a look at a snapshot taken from Node’s source code:

function createWorkerProcess(id, env) {

// ...

return fork(cluster.settings.exec, cluster.settings.args, {

cwd: cluster.settings.cwd,

env: workerEnv,

silent: cluster.settings.silent,

windowsHide: cluster.settings.windowsHide,

execArgv: execArgv,

stdio: cluster.settings.stdio,

gid: cluster.settings.gid,

uid: cluster.settings.uid

})

}Source: lib/internal/cluster/master.js

As you can see, the cluster is directly dependent on the fork() method, and if we’ll take a look

at the fork() method implementation we’ll see that it directly depends on the spawn() method:

exports.fork = function fork(modulePath /* , args, options */) {

// ...

return spawn(options.execPath, args, options)

}Source: lib/child_process.js

So eventually, it all comes down to the spawn() method; everything that node provides us with

which is related to processes is just a wrap around it.

There’s definitely more digging to do when it comes to the world of processes, in relation to Node’s internals and outside it in relation to the OS. But after reading this you can make a practical use of one of Node’s greatest features and unleash its full potential. Keep on reading the docs and investigating because it can definitely elevate your backed skills, and if you have any further questions or topics that you would like me to write about (in the JavaScript world) do tell.

Join our newsletter

Want to hear from us when there's something new? Sign up and stay up to date!

By subscribing, you agree with Beehiiv’s Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.

Recent issues of our newsletterSimilar articles

The complete GraphQL Scalar Guide

Knowing how native and custom GraphQL Scalar works enables building flexible and extendable GraphQL schema.

Scalable APIs with GraphQL Server Codegen Preset

Structuring GraphQL server the right way enables many teams to work in harmony while minimising runtime risks.

JavaScript runs everywhere, so should your servers - here is how

A new way to make any Javascript server platform-agnostic.

Announcing GraphQL Yoga 2.0!

Fully-featured GraphQL Server with focus on easy setup, performance and great developer experience