This is how our brain detects shapes

And so Shall the Computer…

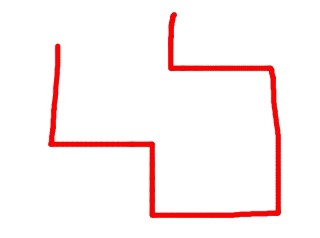

There was this time I was trying to create a studio where you can sketch primitives and transform them with touch gestures (credit to Guy Manor for the idea ❤). As part of my work I had to create an algorithm that could normalize drawn shapes, because there’s no use to a set of dozens of vertices which together look like nothing but one big mess. The result can be seen in the GIF above. Looks pretty nice right?

In this article I’m going to go through the algorithm that I used to detect shapes. I’m aware of the fact that in the real world there are much more parameters, and it can be much harder sometimes to detect certain shapes, especially the abstract ones which are made out of arcs, but this algorithm still works well and is useful for most use cases. The algorithm assumes that we work in a 2D space and will produce a set of normalized vectors, a circle, a rectangle, or any pre-defined shape in a given shapes’ atlas. If you want to cut straight to the chase then a JS implementation of the algorithm is consumable in the following Git repo: github.com/Appfairy/shapeit.

Without further or do let’s go through the algorithm!

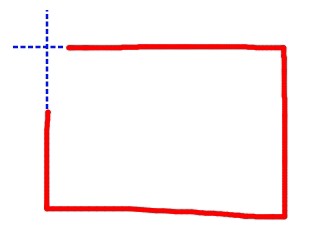

- If a given sketch is open, try to lengthen first and last vectors in hope to find intersection and create a closed area.

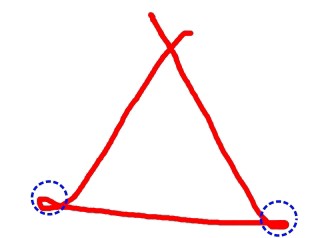

- Look for all the closed areas within the given sketch and reduce all the areas which don’t pass a certain threshold. If the area is less than a constant value, splice its vertices.

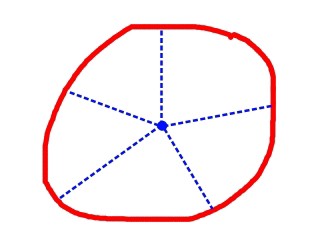

- Assuming that we’re down to only a single area, try to match it with a circle by calculating the standard deviation of each radius from the center of the shape to one of its vertices. If standard deviation is less than a constant value, it must be a circle.

- If a circle was not found, reduce the level of detail of the polygon by splicing vertices which cause an insignificant angle change.

- Sometimes we might be down to a single vector or a set of vectors in case there was no closed area in the given sketch.

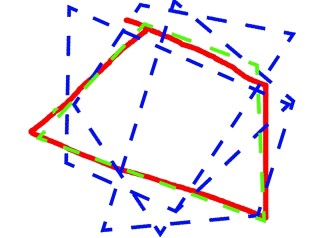

Now this part is slightly more complicated. We’re going to try to match the normalized polygon with one of the shapes in the atlas of pre-defined shapes. Besides of actually detecting whether the polygon represents a certain shape or not, we’ll also need to take the found match in the atlas and transform it to match as closely as possible to the average properties of the polygon. So our atlas may consist of any closed 2D polygons such as: A triangle, a rhombus, a trapezoid, a hexagon, etc.

Shape matching is done with score calculation based on different parameters. The higher the score is the more likely we’re to accept a certain shape is the intended one. We will calculate the score of the drawn polygon relatively to all pre-defined shapes in atlas with the same amount of vectors, and if the highest score is greater than a certain threshold, then that would be it. A score calculation for a shape will be done based on the co-sinuses of the angles between the vectors and the ratios between the vectors.

Note that order matters. It doesn’t matter where the series starts or ends, as long as there’s consistency between the values, that’s how we’re going to evaluate the score.

Since shapes with more vectors are more likely to receive a lower score, in nearly all cases, we will use a dynamic threshold which will increase or decrease itself based on the target amount of vectors. After testing different variations of the calculation method, starting with the most naive one — a linear method, I’ve reached a conclusion that a radial-exponential one would be the most accurate for the use case:

function getScoreThreshold(edgesNumber) {

return Math.sin((Math.PI / 2) * thresholds.minShapeScore ** edgesNumber)

}Once we’ve determined what shape does the polygon match to, we will start a process of trying to transform the pre-defined shape to have properties as closely as possible to the polygon’s: Scale, angle, direction and position.

- For the scale we will simply calculate the average length of all vectors and divide the 2 values to find the right multiplication

- For the angle, we will repeat the same process, but in addition, we will try different variations

of radians (let r the average radian of the polygon):

r, -r, π + r, π - r, r + .5π, -r - .5π, .5π - r, 1.5π + r - We will repeat angle matching for a mirrored version of the shape aka a different “direction”

- We will position the scaled, rotated and (potentially) mirrored shape and position its center on top of the drawn polygon’s center

- Out of all transformed shapes with different angle variations, we will take the one whose average vertices’ deviation is the smallest compared to the drawn polygon’s vertices

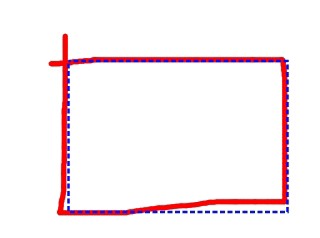

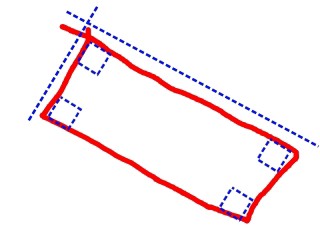

It might be very possible that we haven’t found a matching shape in the atlas! In which case we can return the normalized polygon, unless, it has 4 edges. If our polygon has 4 edges we should try to match it with a rectangle.

First we will try to determine whether the polygon is intended to have 4 right angles by calculating all the co-sinuses and comparing their evaluated score to a certain threshold. If indeed we have a rectangle, we will normalize it by calculating its average vertical length and horizontal length. Once we have a new base-shape we will repeat the process of shape matching against the atlas.

So that was the shape detection algorithm in a nutshell. All I did to come up with it was putting the process that goes through my brain in to code, and the result is detailed above. If we would to add another layer to the algorithm to make it more life-like, it would probably be a deep learning algorithm to detect new base-shapes to fill out the atlas. Maybe I will write about it in my next article ;-)

Join our newsletter

Want to hear from us when there's something new? Sign up and stay up to date!

By subscribing, you agree with Beehiiv’s Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.

Recent issues of our newsletterSimilar articles

The Guild - Rebranding in open source

The Guild is doing rebranding - The open source way

Announcing Accounts.js 1.0 Release Candidate

Introducing Accounts.js 1.0 Release Candidate, an end to end authentication and accounts management solution.

Nextra 3 – Your Favourite MDX Framework, Now on 🧪 Steroids

MDX 3, new i18n, new _meta files with JSX support, more powerful TOC, remote MDX, better bundle size, MathJax, new code block styles, shikiji, ESM-only and more

Building Open Source GraphQL Security

Learn how open-source boosts GraphQL security and explore defensive and offensive tools, resources, and best practices to protect your GraphQL APIs.